3

Friend or Foe ?

孰敵孰友?

Foo Hong 符大煥(31-73)

Sun-Hoo Foo 符傳孝 (32-74-109) 1-2

March 14 2022

In March 1942, a Chiang Mai friend, NiPuQing( 女不清) who shared dad’s room at night advised him to work for his uncle who managed two rubber plantations, 2000 acres total ( 3.25 square miles, >⅓ the size of Alpine, USA ), controlled by Japanese. His uncle had to manage the workers and inventory, so he needed a person to keep track of the transactions. Dad, a 20-year-old young man with some high school education and retail experience selling vegetables and chicken in the market, was an ideal candidate. The job paid 25 dollars a month, better than 15 dollars for the workers tapping the rubber trees.

Although the rubber would be shipped to Japan‘s factories, the work did not directly hurt the community or individuals and so he was not a "Japanese traitor” should he take the job. Working there would be safer than the chaotic outside world.

After 3-4 months, NiPuQing’s uncle was arrested, suspected of stealing the company’s sugar and selling it to local coffee shops. Dad went to the jail and brought him food every day for the next 10 days or so until he disappeared. Dad was quite upset about this “ life’s uncertainty”. Soon, he was offered the managing job. One day, a young man, whom he had met only once in a friend’s coffee shop before the Japanese invasion, came to his office. He placed a pistol on the table, told dad it was difficult in the north, and people were sick and needed help. Dad understood between the lines that they were an anti-Japanese army. He offered him $50 which was his salary for a month.

He was laid off several months later for “no experience in dealing with processing the rubber product”. This was a conspiracy by an Indian coworker with a Japanese to get the job. When he went to pick up the food allowance certificate, a must to get a food allowance, he met a Japanese acquaintance who had advanced in rank. He asked if dad would like to manage a farm and pasture(華帝灣農牧場) 8 km northwest of Kuala Lumpur.

That shabby farm was 264 acres and had 400 Chinese workers ( 300 Hakka, 100 Hokkien) and some Indians. The pigpen had less than 100 sows. There were 50 yellow cattles. They also planted cassava and sweet potatoes. There were three sheds for workers to rest and eat lunch from home but no kitchen. The workers started work at 8 am and went home at 5 pm. Dad’s salary as manager, head of the farm, was $50 a month. Foremen made $30 dollars and workers were paid 50 cents each day, $15 if they showed up all the workdays that month (that would be $10 plus a $5 bonus. 50 cents was good for a cup of coffee but not enough for a bowl of porridge in the shop). Dad had to wake up at 5 am then cycle to work from where he lived in Setapak(文良港), Kuala Lumpur, 8 Km away.

Dad worked to improve the farm and pasture so life for the workers could be improved. Eventually, he managed to double the pigpen to 200 sows and 100 yellow cattles. He cut down 100 acres of old rubber trees to make land for cultivating rice. This effort failed because they used 120 bags of seed and the return was only 40 bags. They planted more cassava and sweet potatoes instead. They developed another 10 acres of land for vegetables. He distributed the extra cassava, sweet potatoes, and vegetables among the workers. Several weak and defective kettles and pigs a month were also shared among them. He gave 2 piglets to an inspecting Japanese officer one day and got an extra quota for purchasing two extra drums (each 400 gallons) of cooking oil to share. He also rewarded piglets to the hard working men. The old trees logged to develop the land were cut to sell and benefited the workers.

His Setapak neighbor was a Japanese marine officer. Yamamoto was looking for a supply of bamboo screens to protect the goods on the ship deck from the weather. He organized his 60 workers who knew how to weave. According to the contract, if a worker weaves 3 screens a day, he can get $4.5 dollars + 12 ounces of rice or 4 screens for $6 +16 ounces of rice. This extra money was very much appreciated. In 1944, most of the 700 farm/pastures in Malaya were closed, except dad’s farm was still functioning. He was questioned by the Japanese army. Dad's answer was “ If I don’t make it work, how can the workers live?” The farm finally closed in August 1945 after Japan surrendered. He was out of work again.

One afternoon in 1944, while he was chatting with friends in a coffee shop, several young men showed up. One of them, the same person who had solicited $50 from him with a gun, approached and talked to him, asking where and what dad was doing. Dad was suspicious. Sure enough, that man showed up in his residence and said “My captain suspects you are too close to the Japanese and wants to have a few words. He is waiting for you in the coffee shop.” Walking down the slope towards the coffee shop he frequented, he saw a truck waiting for them. Two young men got off the truck to escort him in and drove towards the city. He realized immediately that the man was a traitor. He was kept in a watched third-floor room in the middle of the town. Two Japanese detectives came over and asked if he worked for the Japanese army or if he worked for anti-Japanese forces. His answer was no to either. And he was asked whether he helped the anti-Japanese force. He gave the true answer, he didn't know whether the man was anti-Japanese. At the end, he signed the document. After that, two others and then two more came and asked similar questions. One of them forced him to sign “I am an anti-Japanese warrior”. He refused and was forcefully slapped on the face. Next, one wanted him to raise his arm and jabbed three times at his axilla. (This is not in the book, but I remember he told me that he was tortured and was forced to drink lots of water from a hose.)

He was desperate. No one knew where he was, he was single, kidnapped without a witness. Even if his friends knew he was missing, they would not know where to find him. From the window the next day, dad saw a friend starting the day opening the coffee shop about 100 meters away. He waved his hand but didn't catch his friend’s attention.

And then he got this idea: He knew the friend’s coffee shop in Setapak where he lived was next to a police station, equipped with a 24/7 telephone. He convinced the guard to call the police line and asked his friend to the phone, so he can tell them how to manage the farm in dad’s absence. The guard thought it was a real necessity. Instead, dad talked to 符大欽(his relative) in Hainanese for help (this is so helpful to know your native language - the guard did not understand). Dad asked him to phone Mrs. Yamamoto to inform her husband that dad was sequestrated in the 3rd floor of a Japanese shop at 諧街 High Street (now Jalan Tun H. S. Lee), Kuala Lumpur. ( around the site of Sin Sze Si Ya Temple) .

Not long after the call, he was invited to have breakfast downstairs. About two hours later, officer Yamamoto stepped out from a Marine sedan. It stirred up some commotion. After reporting to Yamamoto, the Taiwanese manager asked the guard to bring dad down. Yamamoto smiled and said to dad “ no problem, you may leave with me .” He drove dad home.

P.S.

Some afterthoughts:

Dad wanted us to know his life history, and to learn from it. He left some voice interview recordings to Yang. Later I tried too, however that was in the last several years of his life and he tended to circumvent and some memory had left him. These are in the archives waiting to be edited.

This is from dad’s autobiography in Chinese, recorded and edited by 王錫鈞, My part is adding photos, making it into a book form, published online too in blurb, March 2009. (Dad passed on March 8, 2014 at age 92). One can purchase that edition from blurb.com or view from the Blog. I am not sure when it can be translated to English and I think it is important for me to write down my understanding of his life before I lose it too. The autobiography was done in his 70s, one can be amazed by his memory.

Dad lives life the best he can, no matter how bad/good the circumstance is.

He always thinks to create opportunities for others and help them in whatever he can.

He treats people fairly, keeps his promises, and focuses on his work. He appreciates and remembers people’s kindness

He gets help in return

I am not sure what I would do in his shoes.

He is an ordinary person, finding himself in this cruel war trying to survive.

He is not in the army or resistance force to fight the Japanese. Should he or could he?

A “passionate” young man, supposedly an honorable man, put a pistol on the table and asked for help. Dad gave $50, not told but knew he was helping a resistance force.

He managed a Japanese plantation and pasture supplying raw material to the war under Japanese control. That is a more secure place to be and he can make enough to survive.

He fulfilled the job obligation, perhaps more. Everyone struggles just to survive. He looks out for his workers. The results win him some reasonable Japanese friends. They are the enemy but also are thrust into the war involuntarily (身不由己)。

The turncoat man (friend?) kidnapped him perhaps to fill his quota to justify his new job and then a Japanese officer (enemy?) rescued him.

I quote the dollars from the book just to remind you how life was and how life is today. The minimum wage today, the living standard, and the way we live are so much different.

Dad survived, hundreds of similar nice people perished without a trace - those people who vanished may be stronger, more intelligent, better educated but somehow in the wrong place/wrong time, not lucky to have help in time. His life story teaches me about life and how best to live. I appreciate his wisdom more now.

Each life is a raindrop falling on water, the ripples propagate and are felt forever.

This is what I wrote on his book in Chinese:

https://www.blurb.com/books/591551-autobiography-of-foo-hong

我很高興家父能將他一生 的經歷寫下來給我們共享。在他們那個大苦難的時代,他靠著一顆善良,克苦耐勞,努力向上,愛人如己的心去處世。得到許多親友的幫助,也幫助不少人。要不是那個環境的限制,他一生的成就肯定會更不一樣。

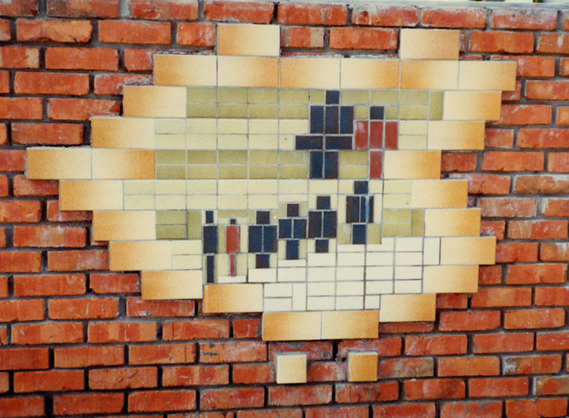

封底的回教堂是他五十年代的傑作,五十年后還是那麼聖嚴。他念念不忘祖國,幸幸苦苦的和媽媽把我們六兄妹扶養成人,讓我們站在他們的肩膀上,看的更遠。封面書頁上的圖片,是他以磁磚切割拼接而成的墻飾,可以想像他一心為家為鄉的情懷。

他整理家鄉,同時接合在新加坡重印的族譜,親自把七十三代的祖先一一找出來。重抄《朱柏盧治家格言》,《羅洪先醒世詩》就是要給我們做為借鏡。他極重友情,我本來想把他多年來的好友照片都印出來。可惜因為照片解析度不夠,只好作罷。

言輕意重,在此與你重溫家父的一生。

符傳孝Sun-Hoo Foo (32-74)

16 February 2009